In this edition, GCIR President Marissa Tirona speaks with Arcenio Lopez, Executive Director of Mixteco/Indigena Community Organizing Project (MICOP). Read on as Arcenio shares his thoughts about building power for Indigenous immigrants, the importance of forging alliances with other Indigenous communities, and how philanthropy can support and strengthen the work of Indigenous migrants.

Please tell us about yourself and your organization. Can you describe the communities served by your organization?

I was not born in the U.S., but my parents traveled seasonally from Oaxaca to work in agriculture in California starting in the 1980s. They shared stories with me about life in California, so I had some idea of the future that awaited me when I migrated, with both its opportunities and its challenges. When I first came to the U.S. in 2003, I was 21 years old, I did not speak any English, and I worked in the strawberry fields.Determined to create a better future for myself and my family, I worked and studied with discipline. Now I am the proud father of two daughters, and a vision I had when I came to the U.S. was realized this year when my daughter graduated from UCLA. My younger daughter is beginning her sophomore year at UC Davis. I have also been able to complete my college degree here at California Lutheran University.

Working in the fields, I found that many of my colleagues were Indigenous migrants speaking only our native languages such as Mixteco and Zapoteco. Often, they were discriminated against and taken advantage of. Seeing the struggles they faced, I wanted to make a difference and help stop these abuses, and that’s how I found Mixteco/Indigena Community Organizing Project (MICOP). After I became involved with MICOP I came to value my indigenous identity and language, and I started speaking Mixteco. I learned about community organizing, the dynamics of power, and the systems of oppression and racism that have kept us (Indigenous people) excluded for so many years.

Founded in 2001, MICOP supports, organizes, and empowers Indigenous migrant communities in California's Central Coast with access to interpreters, leadership development, classes for parents, immigration legal assistance, and advocacy for Indigenous rights.

The Indigenous migrant communities in California are very diverse. According to the 2009 Indigenous Farmworker Study (IFS), more than 160,000 Indigenous migrants work in the California agriculture industry. I believe that at least six out of ten farmworkers in California are from Indigenous communities. We speak our native languages that are different from Spanish and English. Our Indigenous languages are not dialects, they are languages and each one has multiple variants. We are part of 68 Indigenous nations from Mexico.How do you define power for the communities you serve? What is your strategy for building power and what have you achieved as a result?

When I first got involved with MICOP I knew I was helping people, but I didn’t see organizing or building power as something that was possible for us. I had internalized the message that, since we were “illegal”, we shouldn’t do anything that might put us in danger, including organizing for change. At MICOP, we overcame this narrative and were motivated into action by the discrimination we faced as Mixteco people.

Since then, I’ve seen how our communities can bring about change when we embrace our identity and culture and when we learn about the history of Indigenous people. At MICOP, we are thinking strategically about how we talk about ourselves. We used to call ourselves immigrants, but why should we do that when we are on our own continent? We are migrants, people who move. Because of colonization our lands were taken away from us. Our identities were taken away from us. Building power in the Indigenous community means claiming our roots and learning our own history. When I think about what’s been done to us, it motivates me to take our power back.

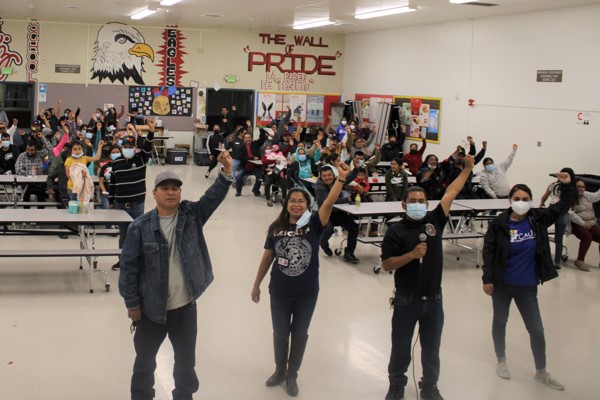

Power building can be a lot of work, but great things can be achieved when we work together. For example, in 2016 we achieved a major language justice victory. The state of California made driver’s licenses available to everyone regardless of immigration status, but many people were not able to access them because they didn’t know how to read and write and could not take the required test. We came together and organized to change that, and now the DMV has interpreters to help speakers of Indigenous languages and allows people to take the test orally.We can’t achieve these kinds of victories until we realize it is not a shame to speak your language, it is an asset.

What are the challenges and opportunities Indigenous migrant communities face within the immigrant justice movement? In their origin countries and in transit? In their interactions with funders?

There is a lack of awareness of just how many Indigenous migrants there are in this country, and a lack of awareness means a lack of support. Our Indigenous communities are often made invisible as we are classified as Hispanic and Latinx, and it is a challenge to demonstrate to funders and political leaders that we are a distinct and significant community – a community with needs but also with power.It is ironic how our culture is appropriated while we are not at the table. I keep hearing from the environmental justice movement that we should “learn from Indigenous people” and “take care of mother earth”, but we are not a part of those conversations. It's the same in immigrant justice spaces – there is just not enough room for our voices to be heard.

If we’re going to change that, we need to change the conversation. We need a narrative about building alliances with indigenous communities here and across the continent instead of telling a narrow story about a fight for work visas or employment status. At MICOP, we are thinking about how to build relationships and trust with other Indigenous communities because they are dealing with the same systems of oppression. We need to come together to heal, to create community, and to fight.

What do you need from philanthropy to make that vision possible?

Often when there are crises foundations want to support the highest profile nonprofits, but those organizations don’t know how to do outreach to our communities, and they don’t have our trust. When the Covid-19 pandemic struck, suddenly philanthropy was willing to support us and other organizations like ours. While we appreciated that support, it is unfortunate that we have to wait until disaster strikes for our communities to get help. We need long term support, including multi-year grants, so that indigenous communities can be ready for the challenges that will inevitably come our way.When we do get support from philanthropy, it can feel like we are not trusted to manage the funds, and organizations serving our community may not qualify for support if it is judged that they don’t have enough capacity. But if we don’t get support, how will we build that capacity? When I first started working with MICOP I thought nonprofits were charities designed simply to help poor people, and I saw our work from a place of scarcity. Now I understand that we need to think bigger and invest in capital, buildings, and administrative costs. It is important for us BIPOC-led organizations to able to do that: to make investments that put us in a position of strength to serve our communities for the long term. There aren’t a lot of Indigenous migrant-led organizations – we can count them on our fingers. But there are many hometown associations that are doing important work for their communities but that do not have a formal structure or 501c3 status.

Philanthropy could help them build their capacity by providing unrestricted general operating support, but that would mean rethinking who qualifies for support and how success is measured.

To build power for Indigenous communities, we must think broadly about how to address a variety of needs. At MICOP we have over 20 programs, including community organizing, policy and advocacy, a community radio station, and direct services that include mental health and case management. For us, part of having power is being healthy as a community and being connected to our culture and language. We need investments that meet those needs and recognize that this is long term work to bring about systemic change. Systemic change doesn’t take months, it takes years.

What is your vision for the next five to seven years, and how will power building help realize that vision?

As an Indigenous organization, we sometimes struggle to navigate what the nonprofit system requires in a capitalist context while following our own values, strategies, and practices. As we move forward, we are working toward having a board of directors that reflects the people we are serving. I have learned that a board is often made up of wealthy people who donate, who have resources, who can ask other people for money and help with fundraising. A Mixteco farmworker might not be able to do that, but they have a commitment to their community. We want to be welcoming to those folks, to mentor them and work with them. We’re not just serving Indigenous communities, we are working with and for Indigenous communities. We want that to be reflected in our board and staff.

A promising trend is that youth from our communities are now going to universities, and many of them are studying linguistics and looking to come back after their studies and work with their communities. We need to think about how to support this new generation and put their knowledge and energy to work as we welcome them back.Another priority for us is promoting entrepreneurship for undocumented people. We need to have a conversation about how to help folks start their own businesses so they can be the owners of their own destinies.

Lastly, I see a big opportunity in organizing together with U.S. citizen Indigenous communities. We should be helping them mobilize their voting power. We started initial conversations with local Chumash leaders, but we need to grow this relationship and create a strong partnership with our indigenous brothers and sisters. We need to start a healing conversation. There is so much healing we need to do as indigenous people on this continent.